The Myth About Money, Credit and Gold

The standard version of how money came to be goes like this: First, there was negotiate. (A handful of nails for a pint of ale!) Then, together came various forms of money. An evolutionary derby eventually crowned gold and silver as the supreme money.

And finally, credit (or debt) was born. This is the pinnacle of man’s ascent from knuckle-dragging barterer to tie-wearing mortgage holder.

It’utes a nice little story…except it’s completely wrong.

Busting the ‘Founding Myth’ of Economics

‘Our regular account of monetary history is actually precisely backward,‘ writes David Graeber in Debt: The First 5,Thousand Years. ‘We did not begin with barter, discover money and then eventually develop credit systems. It happened precisely the other way around.‘

Graeber’s book Debt came out in 2011. I didn’t pay much attention to it then. After all, who needs to study another book about debt? But Graeber is an original thinker and offers a perspective you’ve probably not really seen, since Graeber is not an economist. So he draws from unfamiliar wells on the topic of money and credit.

David Graeber is an anthropologist. He’s studied the record associated with human civilisations. It’s nothing like the actual economists imagine it. Graeber quotes from numerous economic textbooks to show how economists perpetuate the mythic progression of barter, money and then credit.

(My very own favourite, The Mystery of Banking through Murray Rothbard, also opens with the same story.) But anthropologists have long known that the historical evidence does not assistance this view. It’s just that economists seem to have ignored this.

Graeber calls the barter-money-credit story ‘the beginning myth’ of economics. Instead, what truly happened first was credit score. In small villages and communities, trade happened on credit. Graeber presents a lot of evidence about this, which I’ll skip in the interest of space.

I’ll simply say it is convincing. And when you think about it, it’s hard to picture it happening any other way. ‘It’utes not as if anyone actually strolled into the local pub,‘ Graeber creates, ‘plunked down a roofing nail and asked for a pint associated with beer.‘

No. What happened was a person ran up a tabs. When the occasion permitted, a person settled the debt in some way – perhaps with a bag of fingernails or tobacco or a chicken. All across the village, there would be numerous such ‘tabs’ or even, essentially, credits (debts) for all kinds of goods and services. People settled these debts in broadly agreed-upon methods.

The Real Truth

‘To this day,‘ Graeber writes, ‘no one has been able to locate a area of the world where the ordinary mode of economic transaction between neighbors takes the form of ‘I’ll give you Twenty chickens for that cow.’‘

When people resorted to barter, Graeber says, it was usually to conduct trade with strangers, or even with enemies. Negotiate is not even particularly ancient, but found more in modern times within societies familiar with the use of money but lacking actual currency or mintage.

‘Elaborate barter systems often appear in the wake of the fall of national economies,‘ Graeber creates. Russia in the 1990s is an example, when rubles disappeared. And often a kind of currency will emerge instead of the old, such as cigarettes within POW camps and prisons. But all of these are cases when people were already familiar with one form of money and learned to make do without it.

Not all economists overlooked the historical record associated with anthropology. Graeber gives a tip of the limit to one Alfred Mitchell-Innes (1864-1950). He was a Uk diplomat, economist and author.

While serving in the Uk Embassy in Washington, DC, through 1908-1913, he wrote two essays concerning the origin of money and credit for The Banking Law Journal. (I’ve read these essays, which you’ll find online. The first is ‘What is Cash?’ and the second is ‘The loan Theory of Money’.)

Mitchell-Innes laid out the fallacies in the popular story. He relied on numismatics and the commercial history of ancient and medieval societies. He showed how credit came first. The sanctity of financial debt spun the wheels associated with commerce. Coins (and money) came later.

‘At this point,‘ Graeber writes of the time of Mitchell-Innes, ‘just about every aspect of the conventional story of the roots of money lay in rubble. Rarely has a historical concept been so absolutely and systematically refuted.‘ Yet the myth endured.

Here, I am barely out of Chapter 2 in my summary of Debt. The book is actually 500-plus pages. I can’t do it justice here, but I’michael going to go to one conclusion that may alter how you think about cash. Graeber, though acknowledging that we can’t know definitely how money came into being, writes approvingly of one historical theory that says states created money to finance wars. As Graeber writes:

‘Say the king wishes to support the standing army of 50,000 men. Under ancient or medieval conditions, feeding such a force was an enormous problem… On the other hand, if one simply hands out coins to soldiers and then needs that every family in the kingdom was obliged to pay one of those coins back to you [to pay taxes], one would, in one blow, turn one’utes entire national economy into a vast machine for the provisioning of soldiers, since now every family, so as to get their hands on the coins, must find some way to contribute to the actual general effort to provide soldiers with the things they want.‘

Admittedly a ‘cartoon’ version, Graeber says that cash markets do spring up around ancient armies. The creation of a national financial debt, then, is essentially a battle debt. A central bank is merely the institutionalisation of the needs from the state and the interests associated with financiers to keep the whole device going.

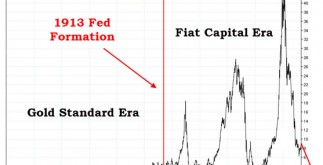

When Nixon took the US off the defacto standard in 1971, it was in part to help finance the war within Vietnam. (Think, too, about what this means for gold. It is no more ‘real money’ compared to ink-stained paper governments turn out. If this sounds like right, gold became money just because states once placed it and made it money and accepted it to settle financial obligations and taxes. Otherwise, it’s just another commodity.) The US financial debt made possible a huge military-industrial complex.

‘The financial debt crisis was a direct result of the need to pay for bombs,‘ Graeber writes, ‘or, to be more precise, the vast military infrastructure necessary to deliver them.‘ Nixon ordered more than Four million tons of explosives dropped on Indochina. In a sense, the US military had been the only thing backing the US dollar – after that and now.

‘The U.S. financial debt remains,‘ Graeber writes, ‘as it has been because 1790, a war debt.‘ It is a debt that cannot, and will not, ever be repaid. It is simply rolled over indefinitely, until the day arrives when something else supplants the US dollar.

In the last chapter (‘The Beginning of Something…’) Graeber concludes that people live in a new financial age, ‘one that no-one completely understands.‘ It is an age of credit score. But unlike the credit associated with old – dependent on trust as well as honour – it is one according to military power and financial debt servitude. It is one held with each other by the threat of physical violence.

How this latest phase ends – as government debts continue to pile up – is the great financial question of our times. Graeber’s book is a thoughtful (and well-written) addition to the actual discussion. I enjoyed this. It challenges long-cherished assumptions as well as makes you think – the mark of the good book!

Chris Mayer

Contributing Editor, Money Morning