How to Raise Taxes in South Africa without being too Taxing

There are strong hints that the South Africa government will raise the value-added tax (VAT) rate rather than improve income tax rates following the release of a good interim report on VAT with a committee led by a good eminent judge.

The reason an increase in the VAT rate is becoming contemplated is that the government desires more money to cover its ever-increasing expenditure. Well, that is not new. A lot more than 100 years ago, Adolph Wagner predicted that this would always be the case. This view has become known as Wagner’utes Law. The question thus gets, once again, how to raise this extra income.

The South African federal government should weigh its choice carefully. It has been understood forever of time that indirect taxes fall most heavily on those who are unable to bear this extra burden. Any increase in VAT will fall heaviest on the poor and middle class. Poor people cannot even afford food, the middle class barely generate enough to pay income tax, and they will be paying double tax.

Understanding the actual canons of taxation

Decisions about tax shouldn’t be made by looking solely at the present. The past should also be looked at. The further back one looks the clearer the present problem becomes and hence so does the solution.

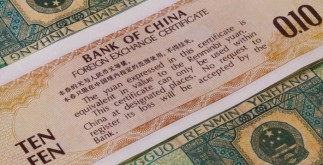

For several centuries, there have been two forms of taxes, which Steve Stuart Mill in 1848 called indirect and direct taxes. Today these are tax and VAT – the Two Ugly Sisters of taxation.

The question is which to increase? The answer is not as difficult as it may appear at a first sight if David Ricardo’s factual observation is actually recalled that taxes fall on either income or capital, in other words savings.

If income taxes fall on savings, the tax system will not survive too long, ending as soon as cost savings have been exhausted, and with that ending the economy. Taxes are only able to fall on income. All forms of taxation are therefore forms of income tax, all attempting to draw out some part of the taxpayers' income utilizing different mechanisms.

The point of leaving is to understand the fundamental concepts on which tax is to be accessed, as applied to taxing earnings. These principles were set out a long time ago by Adam Smith because the canons of taxation. Later they were more clearly explained through Mill.

Oddly, it was only lately that Smith’s first cannon was restated in modern sales terms. The fundamental basis of tax is simple and if imposed in terms of the rule of law needs a single law applicable to all taxpayers. This is what Smith’s first canon achieves. The cost of the necessities of life is subtracted in the taxpayer’s gross income to arrive at taxed income.

Tax is imposed on the taxable income. This fundamental principle was applied from the introduction of income tax in 1799 in Britain until the Peoples’ Budget in early 1900s when the marginal tax system was introduced. The marginal tax system opened up the way for a class battle since tax could after that be differentiated.

The introduction of revenue Tax in 1799 introduced an immediate tax on all earnings. This should have meant that all other forms of taxation become redundant since all income was taxed. Their continued existence came to double taxation. Theoretically indirect taxes, or usage taxes as they were after that called at the time, should have been abolished. However, they were not.

The poor should not be taxed

At current levels, all those who earn less than the amount needed to cover the necessities of life, which in 2006 I estimated to be R120,000 per year for a single person, ought to be exempt from all taxes. The reason behind this is given by Jeremy Bentham and cited with approval by Mill.

The mode of adjusting these inequalities of pressure, which seems to be the most equitable, is that suggested by Bentham, of leaving a certain minimum of income, sufficient to maintain the necessities-of-life, untaxed.

There should thus not be any VAT on the bad at all. The only rationale for the existence of VAT would be that everybody should bear some of the burden of taxation but in this case, VAT should not be a significant income source. To the extent that VAT exists, it is to fulfil the purpose of being the tax of the poor.

If, for example, someone earns the minimum R120,000 a year and VAT is actually levied at 10%, that person would pay R12,000 per annum. That person then does not earn enough to cover the necessities of existence. The VAT is paid in the expense of purchasing food, clothes, and shelter.

Income tax should then start at R120,000 per year at the same rate of 10%. Therefore, a person who makes, say R150,000 a year, would pay the same R12,000 via the VAT system and an additional R300 in income tax – a total of R12,300 per annum.

In all probability that individual would be paying R15 000 within VAT and R300 in income tax, producing a total of R15,Three hundred. The additional R3000 is the double taxation paid by the middle class due to VAT.

The tax burden around the lower income earners because of VAT is actually infinite. Tax burden may be the ratio of tax compensated to the taxable income. Since, in this case, the taxable earnings are zero the ratio is infinite, the tax load is infinite.

The Davis Committee Report raises equity considerations associated with VAT and concludes, “Tax is broadly neutral”. This view is easily dismissed as it continues to be throughout history where it’s always been understood the burden of indirect taxes falls more heavily on smaller than larger incomes.

To avoid the type of misunderstandings set out in the report, a brief history of taxation is important. The mistake of the statement is easily demonstrated. The tax burden is the ratio of tax paid to taxable income. Within the example above the tax load of the person earning R150,000 is clearly heavier when Tax is part of the equation.

Dire consequences

There is a very good chance that if VAT is actually increased, civil unrest will bust out as happened in Zimbabwe whenever VAT was increased to pay for the War Veterans Retirement benefits. For Zimbabwe, it was downhill from there onwards.

The tax burden cannot continue to rise indefinitely because indicated by Wagner. The time must arrive where government expenditure is actually reduced in preference to increasing income taxes. Now is the time to understand this and react accordingly.

Failing this, South Africa will be in the same position Portugal was just before the French Trend. The peasants were paying 80% of their income in tax and just before the revolution, the government of the day was considering ways to boost the tax burden even more. The federal government just did not get it.

South The african continent needs to raise taxes: why a VAT increase would be a bad idea is republished along with permission from The Conversation